Britten Engineering Ingenuity on display at MC Collection 2011.

There’s not one bike out there that’s inspired so many of us, so much as the Britten V1000. For me, there aren’t many days where I don’t think about a detail or general principle of that outstanding piece of Kiwi engineering.

As a bike builder, I’ve seen the movies and read the books about how one garage guy from New Zealand went out and kicked the established road racing world in its ass with his genius low budget construction. But would you believe that, until now, I’d never seen a Britten in person?

I met John Shand a couple of years ago at the Karlskoga track in Sweden when we were competing with a twin-carburettor Buell called “Thor’s Hammer.” He had a Britten cap on his head and talked in a strange slang, so he kept my attention. We ended up talking and out it came that he was originally from New Zealand and had worked for the FIM and been involved with the Britten project before moving to Scandinavia.

So, when I heard that Roberto Crepaldi’s bike, Britten number three, would be on display in Stockholm at the MC Collection and that Shand would be doing a presentation, there was no question that I’d miss it. Finally, I got the chance to have a close look at one of only 10 Brittens ever made.

Last Saturday I saw it for the first time and was instantly fascinated. There is nothing on the Britten that is not needed. Just pure bone and muscle. Form absolutely follows function. What needed to be finished is finished. Where the casting could stay raw, it’s raw. It doesn’t come out in the pictures, but the lean packaging is incredibly impressive.

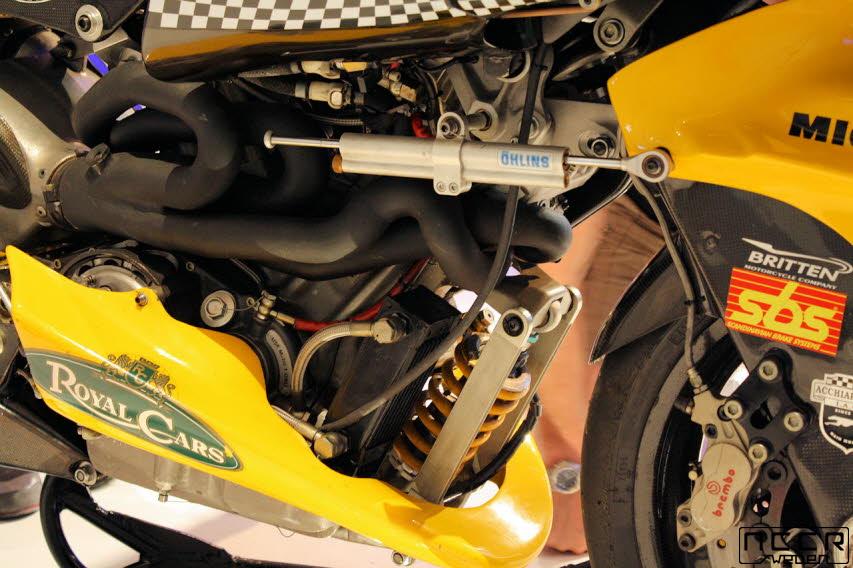

Shand had good stories to tell. One was that John Britten started the development of the bike with a rubber intake port representing the ideal location and shape. A perfectly-shaped intake is the key to making good power, so the rest of the bike was then designed around it. To focus the design around the point of power requires no compromises. Mass centralization and multi-purpose components were then added, helping keep weight down to just 145kg and boost power to 175bhp.

Shand told the audience a lot about the New Zealand garage culture that was based on the fact you needed to wait three months to receive a part from Europe or the US. They arrived by ship. Surely this is one thing that kept innovation sharp, in addition to having a limited budget and the creativity to dream up unconventional solutions.

Today, we engineer bikes using CAE, lay an edgy CAD over that and then proof the whole thing in CFD. Feed all that data into a rapid prototyping machine and we have parts in our hands four hours later. What progress of John Britten’s wire frame technology. But, the question is: what gets you more? $20 in wire or $100,000 in engineering? The answer’s not so clear when what you need is creativity.

Computer work is the result of bits and bytes that are then shaken down by the same computer programs. Most of today’s construction and design processes are based on similar programs designed to accommodate the needs of modern production. Nothing wrong if your goal is mass production, but so often the results being produced by these identical computer programs are identical too. Today’s BMW is interchangeable for today’s Honda and vice versa. The Britten, in contrast, was absolutely different from anything that came before. It answered the question many of us carry inside: what would the perfect race bike, built without any compromises, look like?

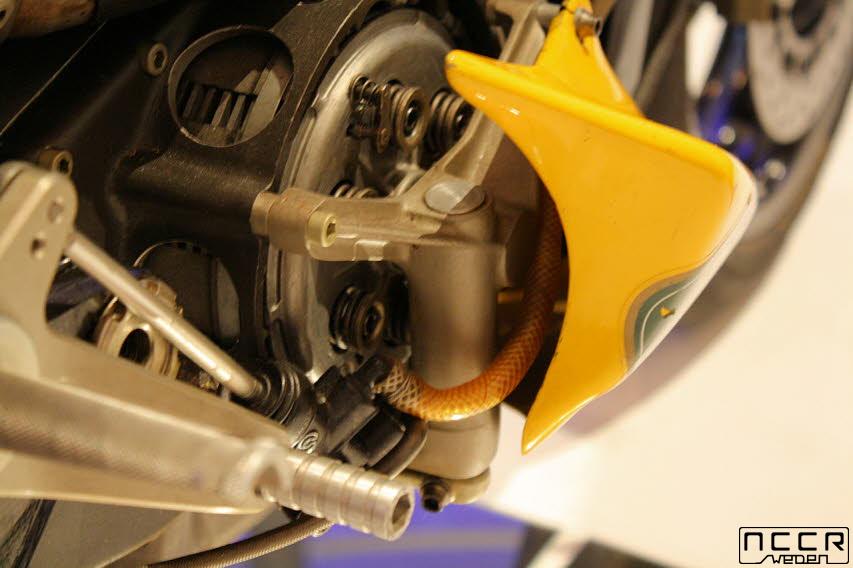

So, John Britten started from zero on a total blank piece of paper and never accepted any technical limitations. What wasn’t available, he and his friends invented. What skills they didn’t have, they learned. Trial and error instead of computer simulations. Garage culture versus think thank.

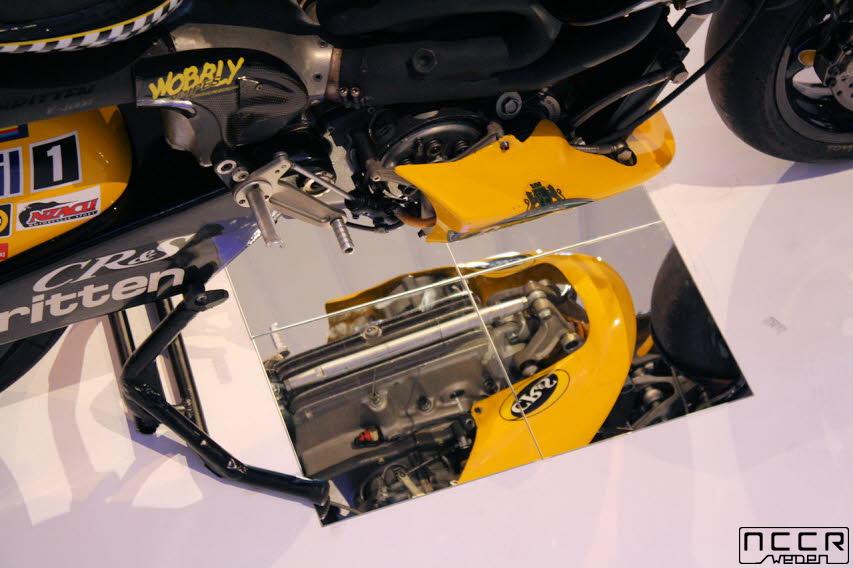

When you see the bike in the flesh, it is shockingly simple. If you don’t want the rear shock’s damping to alter as it heats up, you place it in fresh airflow. If you place the shock in front of the engine, you need to operate it through a pushrod underneath the engine. If you want the swingarm’s weight down low, you make it an upside-down triangle, which coincidentally leaves room for the exhaust. Why clog up the front of the bike with radiators when the seat unit is empty?

Shand told and amazing story about a crew member whose job it was to hold a Husqvarna leaf blower in the intakes to cool the bike as it waited on racing grids.

Today’s bikes use the engine as a stressed member, meaning that it’s part of a group of components that makes up the frame. John Britten simply made the engine the frame, then bolted on a carbon steering head and monocoque rear subframe. That’s it. He even made the engine case the swingarm pivot. No frame, no weight. Even looking at these cast parts today, the quality is amazing.

So with a radically reduced sprung weight, how do you reduce unsprung? If you’re John Britten, you invent the carbon fibre wheel, that’s how. By bike number three, Britten’s ideas were going even further. Have a look at where the brake disc is mounted to the front wheel. The carbon girder forks were controversial with riders, but they won races on them. When you win, you prove that you were right.

This number three bike on display in Stockholm is owned by Roberto Crepaldi, who also participated in the Britten success story. It was him who organized (and I guess, paid for) the European races, including the TT. This bike is painted in the colours of his team, Caferacers and Superbikes. CRS has its own motorcycles, the single-cylinder VUN and X-wedge DUU.

This particular bike is the most raced Britten of all, entering over 50 races in Europe between 1994 and 1997. It finished the TT and won the New Zealand Grand Prix. It’s also called the first Britten production bike because it’s the first that was sold. It started life as an 1,100cc five-valve, then converted to 985cc belt drive and finally had the 999cc, double belt motor installed. In 1994, at the Isle of Man TT, Mark Farmer died when he crashed this bike. Steven Briggs, Shaun Harris and Andrew Stroud also raced it. Stroud took it to Daytona and placed 2nd.

There’s many other stories surrounding Britten. Like the time the engine was given to a large American motor company in the hopes that it’d prompt an engine supplier deal or an out-and-out purchase of Britten Motorcycles. The agreement was that the sealed engine could not be opened, but when it came back a month later, all the seals were broken.

So what can this bike teach us in 2011? A lot. For me, I’ve learned that CNC machining is not everything. John Britten’s secondary chain adjusters are just some plates and a piece of material welded together. Light, simple, cheap, brilliant, easy to make in your garage.

I see today a tendency to overdo things that are less important, simply to follow mainstream convention. That’s eating up our resources and preventing real innovation. Pushing the limit means doing your own thing. I am more than ever impressed with Britten’s innovation and thank him for his inspiration.

Jens wrote this text in 2011 for the US Hellforleather web magazine.

Photos: Birgit Krüper